Preliminary study on the microenvironmental preferences of lichens and bryophytes in the montane forest of El Rey National Park (Salta, Argentina)

DOI:

Keywords:

Bryophytes, lichens, phorophytesAbstract

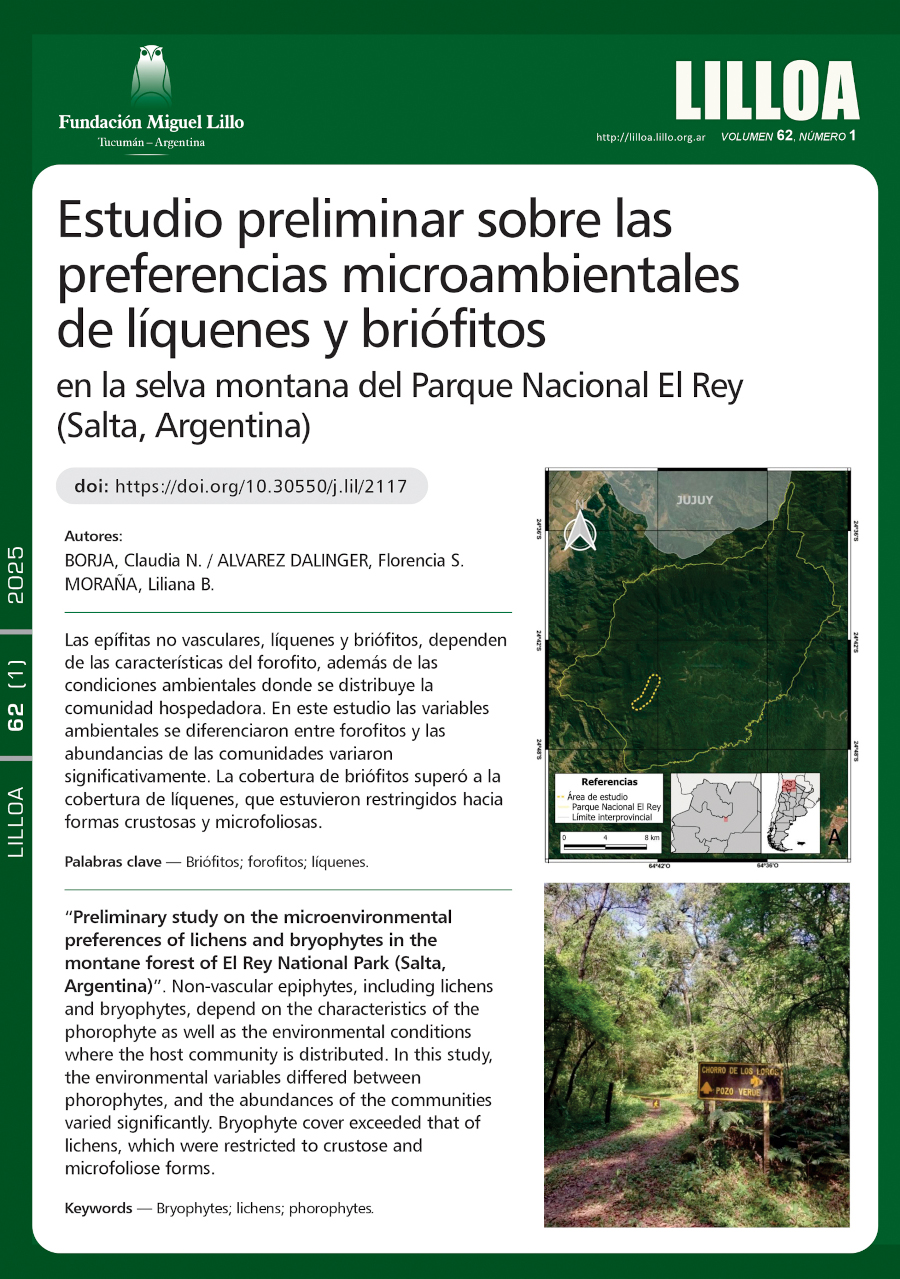

The montane forest of El Rey National Park (PNER) extends along humid slopes between 950 and 1600 meters above sea level, where the epiphytic stratum acquires notable importance, with the presence of mosses, lichens, and small Bromeliaceae species standing out among the vascular epiphytes. Given the importance of the role of epiphytes in these ecosystems and the effect of the conditions that each host intrinsically presents for harboring them, this study analyzed the relationship of lichen and bryophyte communities on two dominant phorophyte species, considering that different types of phorophytes determine specific microenvironmental (microclimatic and microsite) conditions. The study area was located along the Pozo Verde trail. Changes in the cover of lichens and bryophytes were evaluated on two representative tree species, Ocotea porphyria and Juglans australis. For this purpose, a 10 x 100 cm grid was used, placed 50 cm above ground level on each of the cardinal orientations of each phorophyte. The following microenvironmental variables were measured: temperature, humidity, light intensity, diameter at breast height (DBH), and pH. The microenvironmental variables differed between phorophytes: in O. porphyria, the microsite parameters (DBH and pH) as well as temperature were higher, while in J. australis, relative humidity was greater. The abundances of the epiphytic communities varied significantly with the change in phorophyte. Bryophyte cover exceeded lichen cover in both cases, and the limited development of the latter was restricted to crustose and microfoliose forms (microlichens). These differences may be associated with the different vegetative structure, highlighting the importance of the vegetation mosaic present in the montane forest of PNER in preserving shade-loving epiphytic communities.

Downloads

References

Affeld, K., Sullivan, J., Worner, S. P. y Didham, R. K. (2008). ¿Es posible predecir la variación espacial en la diversidad de epífitas y la estructura de la comunidad únicamente mediante el muestreo de epífitas vasculares?. Journal of Biogeography 35: 2274-2288.

Araujo, E. (2016). Sistemática integrada del género “Usnea” Dill.” Ex” Adans. [Doctoral dissertation]. Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Bianchi A. R. y Yánez, C. E. (1992). Las Precipitaciones en el Noroeste Argentino. INTA EEA Salta, 2ª ed.

Cabrera, A. L. (1994). Enciclopedia argentina de agricultura y jardinería. Regiones Fitogeográficas Argentinas. Primera reimpresión. Tomo II. Fascículo 1. Ed. ACME S.A.C.I. Buenos Aires.

Cáceres, M., Lücking, R. y Rambold, G. (2007). Phorophyte specificity and environmental parameters versus stochasticity as determinants for species composition of corticolous crustose lichen communities in the Atlantic rain forest of northeastern Brazil Mycological Progress 6: 117-136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-007-0532-2

Cárdenas Henao, L. M. (2017). Hongos liquenizados: adaptaciones y estrategias ecológicas. Seminario de grado de Maestría. Universidad Central de Venezuela.

Chalukian, S. C., Cusato, L. I. y Malmierca, L. M. E. (2007). Ambientes y flora del Parque Nacional El Rey, Salta, Argentina.

Conti, M. E. y Cecchetti, G. (2001). Biological monitoring: lichens as bioindicators of air pollution assessment - a review. Environmental Pollution 114 (3): 471-92.

Di Rienzo, J. A., Casanoves, F., Balzarini, M. G., González, L., Tablada, M. y Robledo, C. W. (2008). Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina.

Diaz Escandón, D., Soto Medina, E., Lücking, R. y Silverstone Sopkin, P. (2016). Corticolous lichens as environmental indicators of natural sulphur emissions near the sulphur mine El Vinagre (Cauca, Colombia). The Lichenologist 46: 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0024282915000535

Etayo, J. 1998. Aportación a la flora liquénica de las Islas Canarias. iv. Líquenes epifitos de La Gomera. Tropical Bryology 14: 85-107.

Frahm, J., O’Shea, B., Pócs, T., Koponen, T., Piippo, S., Enroth, J., Rao, P. y Fang, Y.M. (2003). Manual of tropical bryology. Tropical Bryology 23: 1-196.

Garnier, E., Navas, M. L. y Grigulis, K. (2016). Plant functional diversity: organism traits, community structure, and ecosystem properties. Oxford University Press, New York, US.

Garrido Benavent, I., Llop, E. y Gómez Bolea, A. (2013). Catálogo de los líquenes epífitos de Quercus ilex subsp. rotundifolia de la Vall d´ Albaida (Valencia, España). Botánica Complutensis 37: 27-33.

Gil Novoa, J. E. y Morales Puentes, M. E. (2014). Estratificación vertical de briófitos epífitos encontrados en Quercus humboldtii (Fagaceae) de Boyacá, Colombia. Biología Tropical 62 (2): 719-727. http://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-77442014000100026&lng=en&tlng=es.

Gradstein, S., Nadkarni, N, Krömer, T., Holz, I. y Nöske, N. (2003). A protocol for rapid and representative sampling of vascular and non-vascular epiphyte diversity in tropical rain forests. Selbyana 24: 105-111.

Granados Sánchez, D., López Ríos, G. F., Hernández García, M. A. y Sánchez González, A. (2003). Ecología de las plantas epífitas. Revista Chapingo. Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 9 (2): 101-111.

Guerra, G., Arrocha, C., Rodríguez, G., Déleg, J. y Benítez, A. (2020). Briófitos en los troncos de árboles como indicadores de la alteración en bosques montanos de Panamá. Biología Tropical 68 (2): 492-502.

Hobohm, C. (1998). Epiphytisce Kryptogamen und pH-Wert- ein Beitragzuröko logischen Charakterisier ung von Borkenober fláchen. Herzogia 13: 107-111.

Johansson, P. (2007). Tree age relationships with epiphytic lichen diversity and lichen life-history traits in southern Sweden. Ecoscience 14: 81-91. https://doi.org/10.2980/1195-6860(2007)14[81:TARWEL]2.0.CO;2

Kelly, D. L., O’Donovan, G., Feehan, J., Murphy, S., Drangeid, S. O. y Marcano Berti, L. (2004). The epiphyte communities of a montane rain forest in the Andes of Venezuela: patterns in the distribution of the flora. Tropical Ecology 20: 643-666. https://doi:10.1017/S0266467404001671

Lakatos, M., Rascher, U. y Budel, B. (2006). Características funcionales de líquenes cortícolas en el sotobosque de una tierra baja tropical. Nuevo fitólogo 172: 679-695. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01871.x

Méndez, P. y Vallejo, M. (2003). Evaluación de la presencia o ausencia de líquenes foliosos corticícolas en las especies Pinus oocarpa y Heliocarpus popayanensis en el Jardín Botánico de Popayán, Cauca (Doctoral dissertation). Fundación Universitaria de Popayán. Facultad de Ciencias Naturales. Programa de Ecología.

Mezger, U. (1996). Biomonitoring mit epilithischen und epiphytischen Flechten in einem Belastungsgebiet (Berlin). Ein Verfahrensvergleich. Bibliotheca Lichenologica 63: 1-164.

Molina Moreno, J. R. y Probanza, A. (1992). Pautas de distribución de biocenosis liquénicas epífitas de un robledal de Somosierra, Madrid. Botánica Complutensis 17: 65-78.

Nash, T. (2008). Lichen biology. Second Edition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Oran, S. y Öztürk, S. (2012). Epiphytic lichen diversity on Quercus cerris and Q. frainetto in the Marmara region (Turkey). Tübitak 36: 175-190.

Pereira, I., Müller, F. y Moya, M. (2014). Influencia del pH de la corteza de Nothofagus sobre la riqueza de líquenes y briófitos, Chile central. Gayana Botanica 71 (1):120-130.

Rincón Espitia, A. J. (2011). Composición de la flora de líquenes corticícolas en el Caribe colombiano. Tesis Magíster en Ciencias-Biología. Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Rogers, R. W. (1990). Ecological strategies of lichens. Lichenologist 22 (2): 149-162.

Rosabal, D., Burgaz, A. R. y Reyes, O. J. (2020). Substrate preferences and phorophyte specificity of corticolous lichens on five tree species of the montane rainforest of Gran Piedra, Santiago de Cuba. The Bryologist 116 (2): 113-121.

Simijaca, D., Moncada, B. y Lücking, R. (2018). Bosque de roble o plantación de coníferas, ¿qué prefieren los lí¬quenes epífitos? Colombia Forestal 21 (2): 123-141. https://doi.org/10.14483/2256201X.12575

Soto Medina, E., Lücking, R. y Bolaños Rojas, A. (2012). Especificidad de forofito y preferencias microambientales de los líquenes cortícolas en cinco forofitos del bosque premontano de finca Zíngara, Cali, Colombia. Biología Tropical 60 (2): 843-856. https://doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v60i2.4017

Soto Medina, E., Montoya C., Castaño, A. y Granobles J. (2023). Patrones de diversidad de epífitas vasculares y no vasculares en el bosque seco tropical. Biología tropical 71 (1): e53522. http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rev.biol.trop..v71i1.53522

Upadhyay, S., Jugran, A. K., Joshi, Y., Suyan, R. y Rawal, R. S. (2018). Ecological variables influencing the diversity and distribution of macrolichens colonizing Quercus leucotrichophorain Uttarakhand forest. Journal of mountain science 15 (2): 307-318.

Zárate Arias, N., Moreno Palacios, M. y Torres Benítez, A. (2019). Diversidad, especificidad de forofito y preferencias microambientales de líquenes cortícolas de un bosque subandino en la región Centro de Colombia. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias 43: 737-74.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Lilloa

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.